The Treasures of Compassion and Complexity

By the time that you read this, I hope that you have voted—or at the very least, have your voting plan ready to go.

By the time that you read this, I hope that you have voted—or at the very least, have your voting plan ready to go.

Before voting, we need to examine the issues, naturally in terms of our own interests, but also from the perspective of the people who are affected most directly by the way those issues are decided. Casting a ballot is a moral and political decision, so we should evaluate each candidate’s character and competence and consider the Church’s teaching to properly inform our consciences.

But voting is not enough. Just going to the poll to vote does not exhaust our participation in our democratic form of government nor does it alone fulfill all our moral responsibilities to each other.

On one level, the outcome of this election doesn’t much matter. Whether Vice President Biden or President Trump is elected, the fundamental problems that our nation faces will remain the same: We will still be stuck in a half-hearted, chaotic response to the deaths of over a million people in a global pandemic. Race and class will still shred our social fabric; raging fires, droughts and superstorms will displace thousands. Neither abortion nor the death penalty will disappear overnight, and chances are strong that the rhetoric rooted in rudeness and bearing fruit in hatred will continue to give sanction to violence against people deemed unworthy of our most basic responsibilities to each other.

The Catholic Church is well positioned to advance the common good by creatively addressing these challenges. We are told the well-instructed scribe in Matthew’s Gospel drew forth ‘treasures both old and new.’ The Church could do likewise by helping us understand the challenges we face and the responses we should make. There are two treasures in particular that come to mind.

The first is compassion.

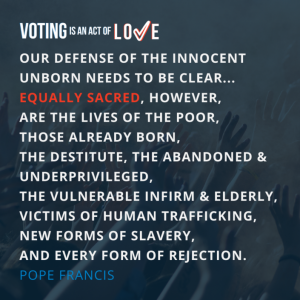

In his recent encyclical, Fratelli Tutti, Pope Francis speaks a lot about the compassion of the Good Samaritan, as demonstrated in the Jesus’ well-known parable. It was compassion that enabled the Samaritan to change his path and interrupt his progress when he found the wounded man by the side of the road. This kind of compassion, Francis contends, should characterize all social interaction, in-person and virtual alike. The Pope is very direct. “The decision to include or exclude those lying wounded along the roadside can serve as a criterion for judging every economic, political, social and religious project” (Fratelli Tutti, 69). The Pope also expands this reflection to a wider context to the level of social policy. “It is an act of charity to assist someone suffering, but it is also an act of charity, even if we do not know that person, to work to change the social conditions that caused his or her suffering (Fratelli Tutti, 186).

If compassion is a force for social change, it also has another effect. It changes us. It opens our minds and hearts to the full range of human experience. As the Council Fathers wrote in 1965 in Gaudium et Spes, nothing that is genuinely human fails to find an echo in our hearts.

When we reflect on our moral responsibilities to each other, attending to others with compassion is the first step in moral decision-making. But it can easily be overlooked or rushed. For it takes time and effort to listen—not just to hear, but to listen—to others’ experience and patiently probe beyond first impressions and instant answers to deeper roots and hidden connections that link our joys and anguishes together.

And so our compassion leads us to complexity, the second treasure that Catholic social teaching offers us. Complexity is the reality that shows why single-issue voting is morally so insufficient.

San Diego Bishop Robert McElroy spoke of this to an audience at Notre Dame University earlier this month: “There is no single issue which in Catholic teaching constitutes a magic bullet that determines a unitary option for faith-filled voting in 2020.” His point about single issue voting is well established in Catholic teaching on public policy, based on the complex nature of the social environment in today’s world. Way back in 1971, Pope Paul VI succinctly described this reality:

In the face of such widely varying situations it is difficult for us to utter a unified message and to put forward a solution which has universal validity. Such is not our ambition, nor is it our mission. It is up to the Christian communities to analyze with objectivity the situation which is proper to their own country, to shed on it the light of the Gospel’s unalterable words and to draw principles of reflection, norms of judgment and directives for action from the social teaching of the Church (Octogesima Adveniens 4)

The US bishops took this very approach in their 1985 pastoral letter Economic Justice for All, seeking to both guide Catholics as they formed their consciences and to cooperate with those who do not share the Catholic tradition (27).

When the issues are complex, so must be the ways that we think about them. Catholic tradition respects that truth. The teaching on a decisive issue like war is a case in point. The Church accepts both pacifism and just-war reasoning as viable moral responses, as long as we hold both modes of reasoning to the fundamental standards of respect for human dignity, the common good, and care of creation. Our tradition grows and changes, as our grasp of transcendent truths deepens and clarifies as the signs of the times change, and new griefs and hopes emerge.

Complexity has always characterized our faith. But that flies in the face of a culture that communicates in short bursts and seeks out divisions that pit ‘them’ against ‘us.

Bringing both treasurers, compassion and complexity, together is what we most need. Compassion for our opponents, for those who think differently and focus on other priorities than we do, could be a first step in strengthening us for the complex work of creating mutually acceptable policies.

After the election is over, there will still be much work to do. We will be doing the best we can with blunt and broken tools, that is, with our own sins and failures. There is also the challenge of being a church whose moral leadership is shadowed by its own abuses of power and money. There will be wounds to bind, changes in our paths, bonds to be created between those who are in need and those who can help them. There will be difficult decisions to make, alliances to build, policies to shape. There will also be—as there always is—the ongoing work of reforming our Church, so that it reflects more clearly the light of faith to all the world. For as Pope Francis wrote in his reflection on the Joy of the Gospel, “Christianity is meant above all to be put into practice. It can be an object of study and reflection, but only to help us better live the Gospel in our daily lives” (Gaudete et Exsultete 109).

If we begin with compassion, and work patiently through complex issues and competing claims, perhaps we will reach—not a false uniformity—but enough consensus to live together with justice and peace.

Image from the Ignatian Solidarity Network.

Mass Times

Sunday at 7:30 AM, 9:30AM, 11:30 AM

Tues., Wed., & Thurs. at 12:05 PM